Miscellaneous1 - The Origin of Life

The great mystery of science is how and where did life originate on Earth?

It is impossible to reconstruct this:

- We may never know how life originated, it could be a fluke. One of those once every so often. Of course, we know how life goes on and that’s something.

- Where life originated may also remain only a conjecture. We know for sure that it could happen on Earth, but whether it does remains to be seen. What possibilities do we have to reconcile ourselves with today?

- Large or small organic molecules can be divided into mostly smaller inorganic molecules or simple atomic compounds. We know for sure that these molecules are found everywhere in the universe (but not in the same quantities). So we can take them apart, so to speak, and why shouldn’t we be able to put them back together? This would go a long way in getting us on the right track. Actually, the investigation is already underway.

- So it is certainly possible on earth. Perhaps not in the condition as the earth is now, but we know that the earth has been in various states in its development where the condition was ideal for generating life. So maybe we should look for similar planets in the universe. Of course, we are already very busy with this. The results are in the news almost daily.

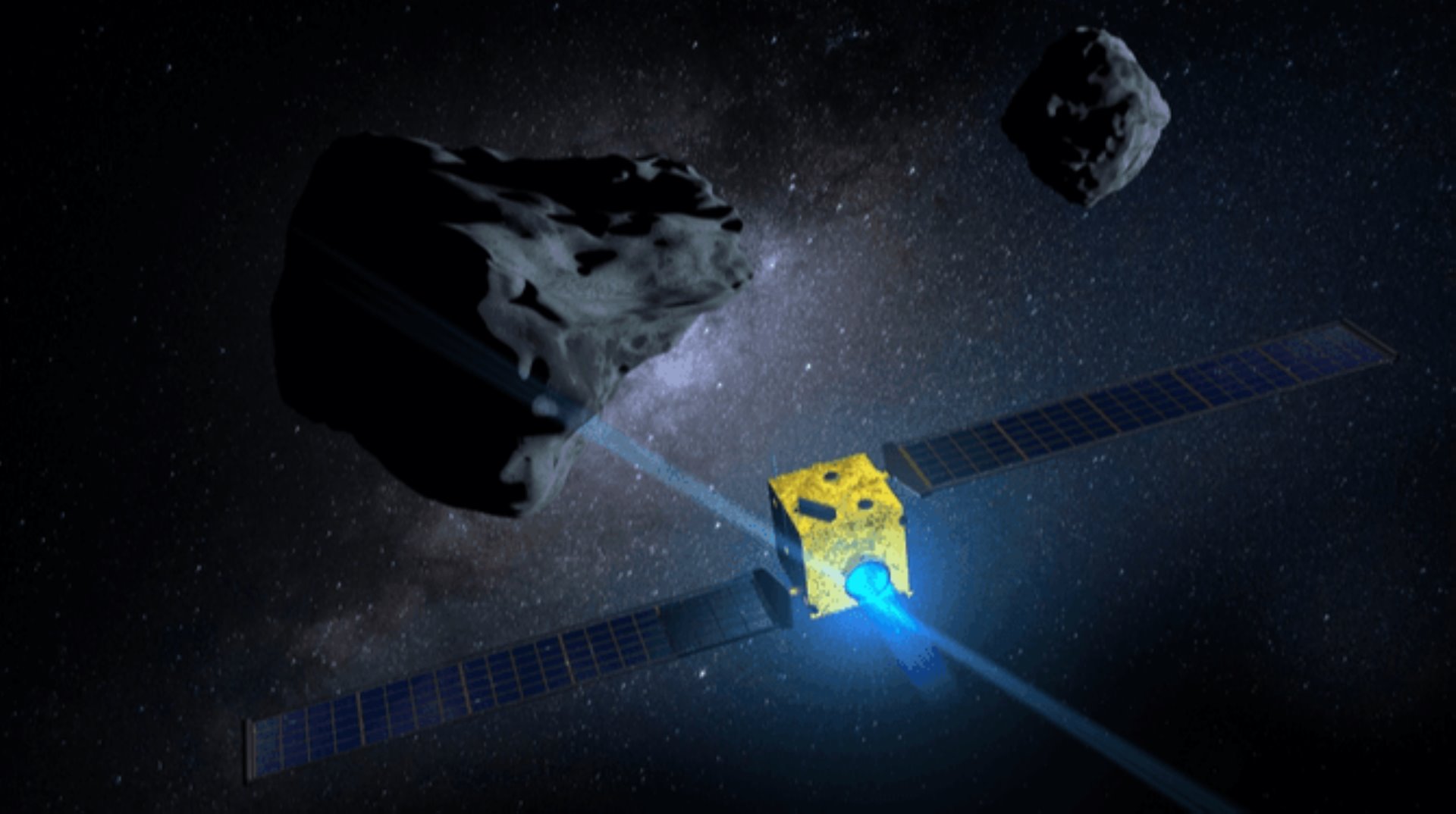

For some time now, scientists have wondered whether the origin of our lives lies on earth? Could it be that a small single-celled organism once hitched a ride on a meteorite and life ended up on Earth? What are we supposed to think about this?

You live somewhere as a little microbe on an alien planet, billions of years ago. You are quietly busy with your own business: ingesting nutrients, excreting waste and producing substances. And suddenly, an asteroid hits. After that, you’ll be launched into space, only to be dropped onto another planet. The Earth. It’s not bad. Maybe not as comfortable as your old home, but you’ll get by. And off we went. This is roughly how an alien organism would have fared if the so-called ballistic panspermia theory were correct. This theory states that the origin of life is not on Earth itself, but on another planet. We have no idea how and where it must have happened. It doesn’t seem obvious, but some scientists are seriously thinking about it.

What is needed?

When a large meteorite hits a celestial body, debris of the crust is flung in all directions. These debris fall back to the surface (sometimes at great distances from the impact area). But if the original impact was really heavy, some of those pieces of debris can reach the so-called escape velocity, escaping the gravity of the celestial body. We’ll see if that can happen. In recent decades, a renewed interest has been sparked as we encounter more and more meteorites from Mars or the Moon on our Earth’s surface. Of course, it’s no coincidence that those two are: they’re our closest neighbor and they’re rocky. The escape velocity of the Earth is 11.2 kilometers per second. But the Moon and the planet Mars are much smaller than Earth. They have a weaker gravitational field and therefore a lower escape velocity (2.4 and 5.0 kilometers per second, respectively). So even in the event of a medium-heavy cosmic impact on the moon or on Mars, it is possible that debris will be thrown into space. First, such debris orbits the sun in its own orbit. But after tens of thousands of years, they can get too close to Earth and end up on the surface as a meteorite. Pieces of the moon or pieces of Mars have landed on Earth. In recent decades, a few hundred of these lunar and Martian meteorites have been found. Their origin is evident from the composition of the stone. We have found them and it is impossible that we have found them all. So there will be many more. So we can no longer speak of a rarity. The fact that the planets exchange material in this way may shed new light on the true origin of life on Earth. Mars was much more similar to Earth in the youth of the solar system than it is today, but the planet cooled faster due to its smaller size and greater distance from the Sun. If life ever arose on Mars, it may have happened earlier than on Earth. If single-celled Martian organisms can end up on Earth aboard a Martian meteorite, it is not inconceivable that all life on Earth is in fact descended from Martian bacteria. The most famous Martian meteorite is ALH 84001, 1.97 kg and found in the Allan Hills in Antarctica. In 1996, NASA researchers thought they had found evidence for the presence of fossil Martian bacteria in this space rock. But everything was revoked, perhaps the future will bring counsel.

Of course, it would go a long way if we had evidence that there was once life on Mars. There is no definite answer yet, they are working it. If it is so, then normal life will take its course, we expect it.

Life may also come from something further than Mars. Interesting are the discoveries of interstellar objects such as Oumuamua (in 2017) and comets such as Borisov (in 2019):

- Oumuamua is without a doubt the first interstellar object ever observed in our Solar System. But it probably wasn’t the first if you know what I mean.

- Borisov has probably never been near a star before. And that makes it the most intact virgin comet that researchers have ever observed. The blueprint of life may still be in there.

Back to another core of our business. To be able to travel from one planet to another, microorganisms must:

- Survive the launch first. The big question here is whether they are already dead as a result of the blow, before they go into the air? During an impact, so much energy is exchanged that rocks melt and even evaporate, not an ideal state I would say. Somewhere one can read that possibly some of the matter that is being launched never came into contact with the asteroid. One speaks of bragging without contact. It will, therefore, not undergo extreme pressure or temperature as a result of the impact. Analyses of Martian meteorites show that they never got completely very hot.

- And then they have to survive the journey through space, at least in harsh conditions. In space, you don’t travel first class. The space is not a nice place to be. You suffer from extreme temperatures, the vacuum and cosmic radiation:

- Extreme temperatures can be survived, even on Earth we know examples of this. There are really extreme conditions here with us where life can endure. Some organisms can withstand extreme conditions for a long time. They do this by going into biostasis, a kind of hibernation. The organism is still alive, but its metabolism has come to a virtual standstill. Water bears, the smallest multicellular organisms, possess this gift. These minuscule creatures are therefore seen as the ideal candidates for space travel. Water bears can withstand temperatures from –272 to 150 degrees Celsius, and are a thousand times more resistant to radiation than we are. In 2007, astronauts took 120 water bears into space. For example, it turned out that water bears can survive in a vacuum for a long time, and are still able to produce healthy young after ten days of radiation exposure.

- To survive the vacuum, they have to hide in the crevices of the rock. A version of a spacesuit.

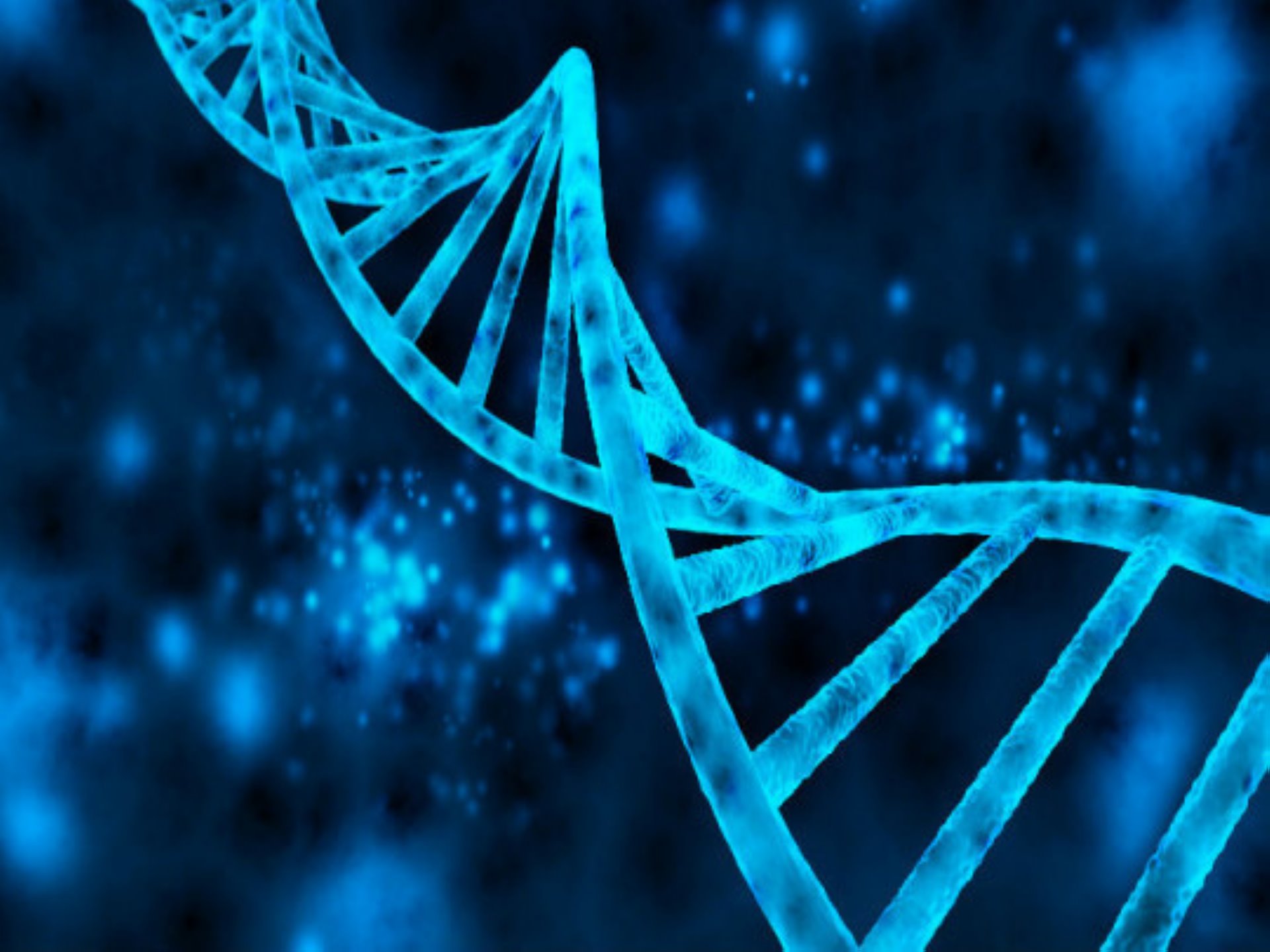

- Even more dangerous than the vacuum is cosmic rays. The high-energy particles from this radiation can damage the DNA in a cell. Cosmic rays can penetrate meters into the rock. In this way, the DNA damage accumulates over time. No good news about that for the time being.

And then: “Can we pass on our lives to other planets or moons in our solar system?”

Here, almost everyone agrees that this is possible. We may already be fully engaged in our space travels. We have already left some rubbish in several places. Just think of the countless spacecraft that were deliberately sent to a surface in order to be able to take measurements of the soil composition, for example, upon impact. And we should even be wary of it:

- For example, we are looking for traces of life on Mars. On this planet, a lot of our earth has already fallen hard or soft. It would be all too crazy if we found life there that would come from us afterwards.

- There are still places in our solar system where terrestrial colonization is a risk. On Enceladus and Europa, for example. The moons of Saturn and Jupiter, respectively. Scientists think that if we throw a microbe into the ocean there, it can survive there just fine. It has everything it needs to grow and reproduce, exobiologists say.

- We can go a step further and state that we can easily cause an ecological catastrophe. A few microbes on Earth could theoretically devastate entire ecosystems. And then we completely miss the mark. After all, we were going to find life, not to eradicate it.

But is all that enough to come to Earth from another celestial body outside our solar system?

Interstellar is far, actually too far. So maybe we shouldn’t think beyond the Mars and Earth exchange. Of course, if we accept it as a possibility, there must have been life on Mars at some point. If there was life on Mars, at a time when both planets were habitable, then it would be almost crazy if that life had not spread to Earth, is an emerging theorem based on probability.

There are reasons to believe that Mars had a time of life. And that at a certain time it would have been even better to stay there than on earth. For one thing, Mars might have been habitable a lot earlier. Because Mars is a smaller planet. After the formation of our solar system, Mars would therefore have cooled faster to the point of liquid water. Life would have had an extra few million years to form on Mars before it became possible on Earth. Mars used to have, in addition to liquid water, an atmosphere and magnetism.

Although little is known about the early days of life on Earth, we know one thing for sure: all life on Earth that we know today stems from a single common ancestor. All life on earth is connected. From the craziest microbe to the weeping willow and the anteater. Each species can be placed on the phylogenetic Tree of Life by biologist Charles Darwin. We can compare our DNA with that of an ancient bacterium, we will see an overlap. This means that:

- If the origin of our life is on Mars, that one immigrant Martian must be the ancestor of all life on Earth.

- If the origin of our life is on earth, then that first earthling is the ancestor of everything.

- If life has arisen in both places and it ever occurred together here with us:

- Then both lifelines were identical and we don’t see any difference between them.

- Then both lifelines were different and one of them died. It’s a pity, but we know that phenomenon in our nature, we are not surprised. One line may have been more primitive than the other. Or one line may have been better adapted. Again, we know that.

Actually, we can only really give a definite answer if we find traces of life on Mars, or on other planets in the vicinity. Then we can see: does it fit on our Tree of Life?’ Only if it turns out that an organism from Mars, genetically speaking, has nothing in common with us, can you almost certainly say that the exchange of life between Mars and Earth never took place. But that doesn’t keep us awake either.

To end on a real note, we can add that possibly not real life itself, but the final impetus of it was passed on. We would be satisfied if we could get one of the following molecules just like that:

- Certain RNA molecules because they can hold information.

- Proteinaceous molecules because they can build up.

- Fatty molecules because they can form membranes. So the material is not yet an organism. But it is on its way to becoming one. We shouldn’t worry about whether life can survive in space. We just have to ask ourselves: can these molecules survive? Will that lump of RNA survive, so there will be a kickstart. We reconcile ourselves with no evidence for, no evidence against.

Comments