Stonehenge Part 3/8 - Special stones.

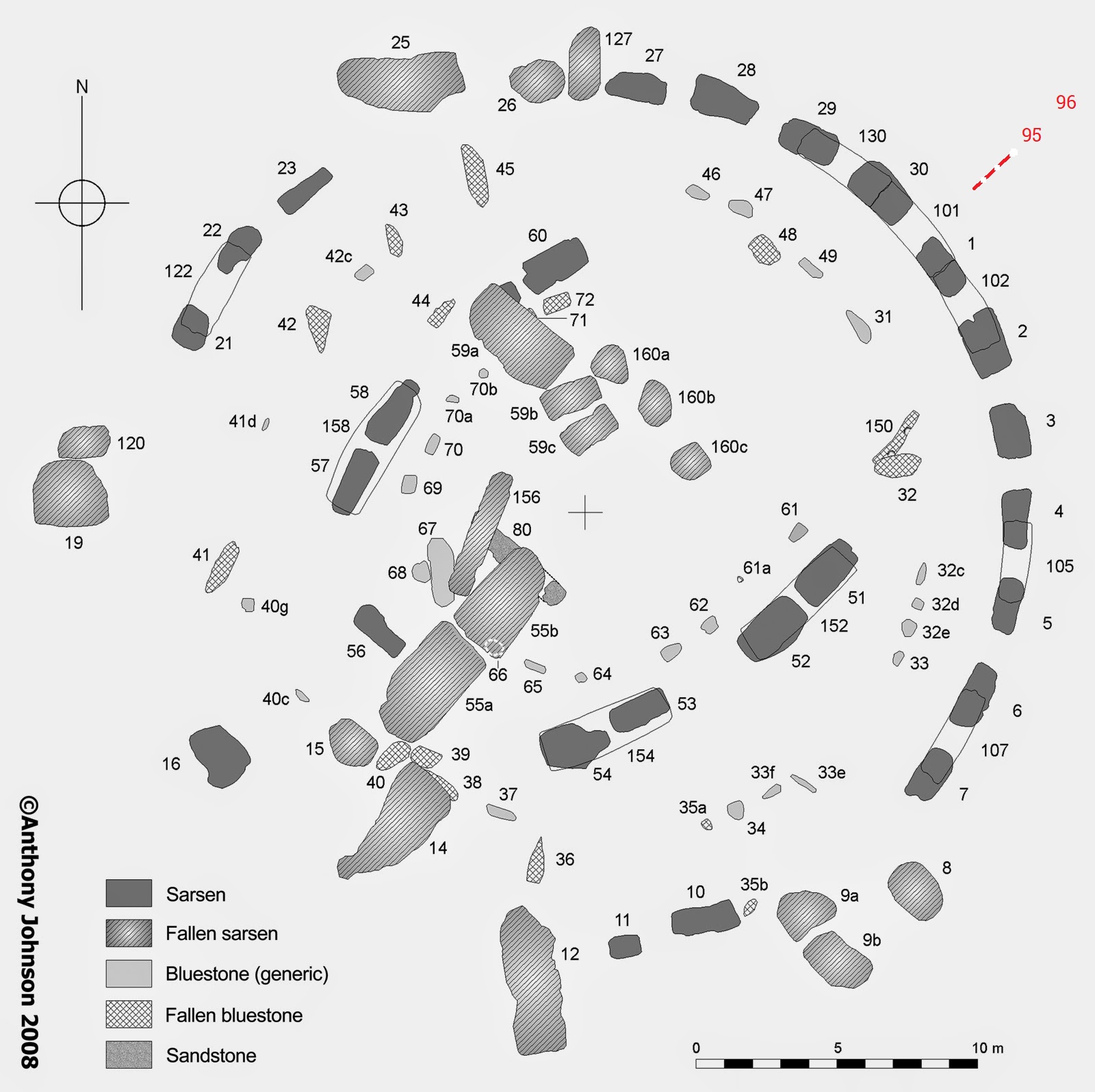

The remaining stones have all been given a number, the boreholes of the missing stones have been localised but not included in the numbering. We pick out a few existing stones in order to present them more clearly. A waterfall of details is created.

Special stones.

Around 2000 B.C. the monument counted more than 160 large stones. Today, a good half of these remain, about 70 stones are missing. There are roughly two types of stones:

- Bluestones from Wales. In humid conditions they colour towards the blue. We may call them bluestone. They are smaller and lighter.

- Sarsens from Marlborough. They colour yellowish in the sun. They are sandstones. They are colossal bigger and much heavier.

Heel Stone 96.

He is on one side at the beginning of the Avenue, perhaps there was a counterpart on the other side of the Avenue, but it has been lost. Both stones would mark the beginning of the Avenue.

It is a rough unprocessed sandstone that slopes (to whole) to the circle. It may also have been named after Helios, the Greek sun god. It certainly forms a kind of key to the monument, during sunrise it casts its shadow to the centre of the circle.

Only with a little good will, one can see the sun rise over this Heel Stone on 21 June. Slightly better is to say that the sun rises exactly between this Heel Stone and its vanished counterpart. Thousands of people gather every year to watch this event:

- However, we must bear in mind that the precession movement of the earth’s axis has shifted the sun’s rise by half a degree over the course of roughly 4500 years that have elapsed in the meantime. So that small concession made the observation more accurate at that time.

- The modern situation is exacerbated by the distant trees that push the sunrise even further to the right.

Slaughter Stone 95.

This sandstone has been lying on the ground for centuries and is half buried with earth.

It lies halfway between the central monument and the Heel Stone. It was probably erected to mark the entrance, it is located near the axis of the solstice.

The name comes from the (false) conviction that it was the stone where sacrifices were made. The red colour was associated with the blood of the victims. We now know that the red colour comes from the iron oxide that is present in that stone and the rainwater in the small cavities shines red.

Altar Stone 80.

This is probably the only sandstone that did not come from Marlborough. Modern geologists situate it from Pembrokeshire in Wales.

The altar stone 80 fell from its pedestal and broke in two when the large nearby Thriliton 55 fell down.

The in two broken large Trilithon 55 (55A) lies on top of the fallen Altar Stone 80.

The ribbon or capstone 156 is also located on top of the fallen Altar Stone 80.

The sandstone got its name when the erroneous story of druids took off.

Ribbon 101.

This capstone forms the so-called gate where the most important sunrise can be seen.

He marks the northeast axis on which the Heel Stone also lies.

The sandstone is estimated at 4,5 tonnes.

Ribbon 107.

This capstone has a brass on one side and a groove on the other.

This connection system allowed the upper circuit to be closely connected to each other.

With some good will we also see that the sandstone has a slight curvature to follow the circumference of the circle.

Ribbon 122.

This capstone broke in two when it fell on New Year’s Eve 1900. Its pillars were skewed in the process.

Restoration took place in 1950. It is clear to see that the sandstone has been put back together again (albeit by invisible bolts).

Ribbon 156.

This capstone lies on the altarstone 80 since the whole Trilithon collapsed.

Notice the hole in this sandstone.

It is the heaviest capstone of all, estimated weight is almost 9 tonnes.

He once spanned the top of the highest structure in Stonehenge.

Ribbon 158.

Sandstone has been at the top again since its restoration in 1958.

He fell over in 1797. So he lay on the ground for 161 years and fell prey to souvenir hunters. These traces are also visible.

Ribbon 160.

This capstone even broke in 3 when it fell down.

The pieces of sandstone were largely covered by the advancing vegetation and soil.

Sarsen 11.

This standing monolith is clearly narrower than Sarsen 10 and doesn’t seem to fit in.

There are 30 Sarsens in a circle. Actually, there are only 29.5 because of the size of number 11. In this way it can correspond to a full lunar cycle.

Sarsen 30.

This monolithic upright has a heavy fracture line at the base.

Maybe this happened during transport or when the stone was erected.

At that time, the builders probably chose eggs for their money, but they did install reinforcements underground. It has been noticed that in this case the soil/lime was higher than elsewhere.

Trilithon 53.

This upright monolith looks almost perfectly rectangular.

At the top it is remarkably smooth, at the bottom there are clearly machining grooves indicating that the work was not yet finished.

There is a small belly in the middle. In order to make the stone smooth everywhere it should actually disappear, but then the firmness of the stone decreases.

If we watch very closely, we see more or less clear notches that may represent an axe and a dagger. From the mandatory footpath the distance is too great to see these symbols. During the annual Solstice you may come closer but then there are always too many people to be able to look at them quietly.

Engraved symbols have also been found on other stones.

Around 1750-1500 B.C. people carved more than a hundred performances in the Sarsens of Stonehenge. Three of them depict daggers, the rest bronze axes. Thanks in part to laser scans, we can find out which types of axes are involved. And because these types correspond to a specific production period, we also know when the images were carved. They are found all over southern England. In the area around Stonehenge they are rarer, but the representations show that they were important objects there as well. Perhaps the depictions are purely graffiti, but archaeologists suspect that people scratched them into the stones to commemorate some of the thousands of dead who were buried under the burial mounds on the plain of Salisbury. They derive that from similar representations in burial chambers elsewhere in Britain.

Trilithon 54.

This upright monolith probably didn’t have enough volume at the top to really fit nicely.

Replacing it with a better one may not have been an option because of time constraints.

Trilithon 56.

This is the highest stone of the monument.

This giant upright monolith has a pearl of a pen at the top. You would like to be less the hole in which that pen fits exactly.

Trilithon 58.

In January 1797, this upright monolith fell to the ground with a heavy blow and broke in two. Heavy rain, a strong wind and a slight earthquake can cause a lot of damage.

This is the last monolith to be restored. Since 1958 it has been flaunting itself upwards again.

There are at least two clear circles of about 7 cm diameter. These are the boreholes hiding the bolts that are supposed to hold the stone together again. The bolts are camouflaged with the original drill cores. By the way, these drill cores have been used to determine the chemical composition and thus the origin of the sandstone.

Trilithon 59.

This monolith upright broke into 3 pieces when it fell: 59a, 59b and 59c.

They are nicely extended in each other towards the centre of the circle.

Trilithon 60.

The inside of this upright monolith is one of the best machined. How many years would it take to obtain this regular shape by hand with a fairly smooth surface ?

His exterior is clearly rougher, so less finished. It is possible that a certain amount of time pressure is lurking around the corner here as well.

Mark that he has been given a solid concrete base on the outside to prevent further mischief. The estimated above-ground weight is 21.5 tonnes.

By the way, his neighbour Trilithon 59 has already fallen over.

Bluestone 31.

Shows on the basic outside the enormous traces of chopping. Almost the abandoned ones managed to take down the stone.

The aboveground part is estimated at 2 tonnes.

Bluestone 62.

This shows the graffiti “FB”.

More he shows the deliberate damage caused by souvenir hunters with hammers over the last hundreds of years.

Bluestone 68.

Displays an elongated vertical groove along the entire length of the side.

This suggests that it may have been linked to another Bluestone in order to get a double volume. The real intention is unclear.

Bluestone 150.

Displays a clear, almost perfect but original borehole.

This borehole suggests that this Bluestone may have been used as a capstone on two other Bluestones. The real intention is unclear.

This overview shows the common numbering of the stones. Of the Slaughter Stone 95 and Heel Stone 96, only the direction is indicated in red.

Comments